How the Inventor of the Computer Killed My Aunt

Uncovering the devastating truth of a 70-year family secret

The beautiful young newlywed, riding pillion on the Triumph 650 on an unlit A-road, laid her head on her husband’s shoulder as, on the black horizon, fireworks sprayed and fizzed in the November air. Elated, she sang a joyful song in his ear. Moments later, her life came to a violent, terrifying end.

Winding down country Lichfield lanes – on their way back to London from Liverpool – the pair had their whole lives ahead of them. Or at least, they should have done.

They were about to literally cross paths with the man who would unwittingly prove my aunt’s killer, and whose identity – whose fame – I wouldn’t discover until 2021.

Aged 21 in 1956, the young bride – married just months earlier – was wearing a three-quarter length orange-red jacket, borrowed without asking from her 19-year-old sister, who had yet to wear it herself, but who would not have minded; sharing each other’s clothes was normal.

Bonfire night, the passenger was also sensible enough to be wearing a crash helmet, though little help it would prove to be.

Her husband, riding the bike within the speed limit of around 30-40mph, moved unwittingly onto a scrappy road surface as he took a slight left-hand bend: a less well-maintained stretch of road, upon which rain still lay from earlier in the day, having evaporated on the previous, well-kept stretch of the lane.

The sudden inevitable skid on the greasy surface turned into a near-90º uncontrollable slide.

Sparks from the motorcycle’s metalwork as it gouged the road were as bright as the fireworks that popped in the dark sky.

That was all the driver of the car heading in the opposite direction, on the correct side of the road, could see: a mobile Catherine wheel, hurtling towards him, with a strange single light shining from the middle.

The driver of the car swerved a little, but there was nowhere for him to go, as the object spraying sparks continued to move further onto his side of the road; the stretch of country lane had a hedgerow to the side, on the perimeter of farmland, so he had to be careful not to careen and perhaps flip it over into the fields. He also had no idea about what it was he was trying to avoid.

The woman who owned the coat was my mother. The woman on the back of the bike, which skidded into the oncoming car, was her elder sister. My aunt died instantaneously, albeit only after a few unimaginably terrifying seconds – how many were there? – as the bike skidded into oncoming traffic.

The man driving the car? Well, he was unknown at the time, despite having already achieved something monumental that, as its relevance only became clear to the world outside the science community decades later. He was a man who worked with Alan Turing, who quickly took advantage of the computer’s invention.

Until late 2021 I knew little of my aunt’s death.

My mum never mentioned it. She flipped out on me when, as a kid, I said I wanted a motorbike when I grew up; I had no idea why I got the reaction I did.

My nan and grandad, working-class Londoners – never mentioned it. My nan began the very slow process of drinking herself to death instead. Part of the silent generation, they said nothing. There was no therapy, just the numbing properties of alcohol.

All I knew, when I was old enough to at least get some answers, is that it occurred in Lichfield, near Birmingham, sometime in the 1950s, and that my aunt’s husband survived the crash relatively unscathed.

I had an impression that it happened on a roundabout, which proved untrue, and that a lorry was involved, which was also untrue. My cousin thought it involved crashing through a shop window.

Such was the pain, none of my family attended the coroner’s inquest. They didn’t want to know the details at the time, and so, three years ago, I was shocked to find relatively informative write-ups in archives of the local newspapers; even if the coroner’s files were sealed for a firm 75 years.

The entire family had suspected my aunt’s husband – my uncle, I suppose, albeit I never met him – of speeding, because that’s what he did around the roads of London, where they lived.

Then, a week after discovering many surprising details of the story on an online newspaper archive, I found something extremely surreal; the strange detail about the hitherto unknown driver that made the story so bizarre.

A series of coincidences sprung up, in keeping with the novel (London Skies) I was writing.

The week after first reading the reports I’d been speaking to my family members, like my mum and her younger sisters (both now in their 80s) – still too sore to talk about it beyond a few minutes – to find out what details they could recall.

At that point I was just trying to find out more about my aunt, and the events surrounding the fateful trip – which had been to see her brother-in-law, who worked as a policeman in Liverpool.

(Another weird coincidence: one of my favourite songs and videos from the late ‘80s was Julian Cope’s China Doll, which I recorded off ITV’s Chart Show and watched repeatedly. Pete de Freitas, drummer of fellow Liverpool band Echo and the Bunnymen, played the motorcycle-courier love interest in the video, but had died on his bike back in England soon after. So, while I was always aware that he’d died on his motorbike, I didn’t realise it was on the very same stretch of road, within a few hundred yards, as where my aunt’s life ended. In his case, however, it sounded like he had a death-wish and drove at great speed.)

That night in 1956, my mum and another of her sisters had returned from the cinema – having just seen the critically acclaimed film Picnic – to find the police at their house. Upstairs, my grandad’s head was slumped on the kitchen table, buried under a towel, as his newly deceased daughter’s mother-in-law said “I hope you’re not gonna blame my boy for this”.

Of course, they did.

My aunt’s husband died thirty years later, in 1986, still a relatively young man himself.

My grandparents died soon after him, in 1987 (my nan) and 1989 (my grandad), in horrible NHS-neglect related ways, never having forgiven him; in the absence of any kind of grief counselling at the time, and with no one able to even talk about it, my nan took the drink, and after 30 years, the drink took my nan.

None of them were ever the same again. I was close to my grandparents (those on my father’s side died when I was too young to remember them), but looking back I only knew two people hollowed out by grief. It wasn’t that they were solemn the whole time, but you just don’t get over something like that. I didn’t even comprehend, as a kid, what it would be like to lose a child; you don’t, until you become a parent yourself.

Now it seems, by all official accounts, my aunt’s husband was not speeding on that fateful night nearly 70 years ago. Knowing that would not have eased their grief, just some of the anger.

The unfortunate man driving the oncoming car on that Lichfield lane was not at that point considered notable. I had no assumptions about him; concluding, as you would, that it was just some utterly random member of the public, like my aunt herself.

Even then, seeing his name in the paper meant nothing to me. I’d never heard of him, or even anyone with his surname.

It was a week before I even thought of googling him, to perhaps, at best, find some family on Facebook. I wanted to ask some questions, about what happened. See if they knew anything.

The results that popped up took me by surprise, to say the least.

He just happened to be the man who, along with two others, essentially invented something now inherent to every single PC. He had been a co-creator of the world’s first electronic stored-program computer.

This was achieved in 1948, soon after World War II. Alan Turing had relocated to Manchester, to join the man, to work on the machine that he’d helped inspire.

The man, alas, died just seven years ago, aged 95. Had he been ten years younger at the time of the accident, or had I discovered the information a decade earlier, I may have been able to ask some questions, were he open to revisiting what must have been a great trauma to him, too.

At the time of the accident, that computer scientist was a mere “civil servant”, according to the newspaper report on the inquest. He had been driving north when the bike left the correct side of the road and skidded under the wheels of his oncoming Standard Vanguard estate car.

That car was driven by a man in his 30s: one “Geoffrey Tootill of Farnborough”, according to The Lichfield Mercury writeup of the coroner’s inquest, which agreed that Tootill was also travelling at an acceptable 30-40mph, on the correct side of the road.

Aside from adding that Tootill was a civil servant, and giving the exact address where he lived, there were no more details about him.

Yet eight years before the fatal accident, Tootill had been one of three men – along with Freddie Williams and Tom Kilburn – to create the Manchester Baby, and then work on the Ferranti Mark 1, “the world's first commercially available electronic general-purpose stored program digital computer,” which followed.

Googling Tootill, the first two results were his lengthy Wikipedia page and a large Times’ obituary. It said he worked as civil servant in Farnborough.

None of my family were allowed to see my aunt at the hospital or morgue, given the extent of her injuries. None attended the inquest, the details of which, I discovered, will finally be fully unsealed in just a few years’ time. Will there be any further details of the events listed?

Do I want to know them?

I do of course.

(And then I may wish I didn’t.)

Also, did Geoffrey Tootill tell his family about the crash, with his three sons all aged under ten at the time?

The accident was not mentioned in his obituaries or on his Wikipedia page, or anywhere else since the newspaper articles in the 1950s; albeit it’s not exactly a crowning achievement to crow about, even if, without doubt, no blame can be put at his door.

But did anyone ever put this together?

(I reached out to his sons via Facebook in 2021, for comment, but received no replies. I don’t think I’d have written this had their father still been alive and refused to speak about it.)

I recently read a book on the history of British computing, Electronic Dreams by Tom Lean, in order to reminisce about my days as a ZX Spectrum addict.

(When I should have been doing my O’levels in the mid-‘80s I mostly bunked off from the rough comprehensive school, and wrote a terrible computer game, that got a couple of kind-on-the-kid reviews. I ended up failing all my exams – the ones I turned up to – bar Art.)

The first chapter in that book deals with Tootill and his colleagues, working on the Baby. Tootill is frequently quoted.

It’s just so strange to me that in 1956 Tootill was unknown; like other computer scientists of his time, his achievements were arcane, and not part of daily life. Had he been well known, it would have surely been a big story, instead of a few paragraphs in the local news.

But it was definitely him; he started working in Farnborough in 1956, according to his Wikipedia page. There can’t have been many Geoffrey Tootills in England, let alone in their 30s, living in Farnborough that very year, working as a civil servant.

I'd loved to have asked him some questions, not that it could have been a pleasant memory, standing over the body of the woman he’d just accidentally killed; a woman who, the coroner noted, suffered lacerations of the brain, despite her crash helmet.

Maybe he never spoke of it again, just like my nan and grandad, and for most of the time, my mum, who still, nearer to the end of her own life, cannot bear to talk about it for more than a minute or two.

The details of the crash also provided some very strange coincidences with the novel (now published) that I had been writing since 2015, and which itself was based on something I started researching way back in 2004, a year before my sportswriting career took off.

It is a novel that involves coincidences over the generations, and its writing also proved full of them.

Part of the novel is set in 1956, and involves an air-crash investigator.

Called Geoffrey. Based in Farnborough.

I’d created this character in 2015, six years before discovering the family story.

As I noted in a post about the book, I was inspired by a misunderstanding of my father fixing planes at Heathrow; instead, he was a mere sheetmetal worker (who patched up the metal on planes).

I grew up in Hayes on the outskirts of West London, in the literal shadow of the EMI factory, and aviation was a big part of my childhood; not flying (I didn’t do that until I was 20), just being close to aircraft.

The coincidence of Geoffrey, working at Farnborough, seemed incredible.

According to the Guardian’s obituary,

“in the mid-1950s he leapt at the offer of a research position from Stuart Hollingdale, head of the mathematics division at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough.”

(He also worked on radar during the war, in Malvern, where the Tomkins’ clan originally hails from, traceable back to at least the 1850s. I went there in 2016 to see the road where my ancestors used to live; instead, the road has gone, and it’s now all modern houses.)

My grandparents also nearly lost a second daughter – my mum – in the 1960s. Less than a dozen years later had their home, which my granddad, as a labourer, had bought and spent years restoring after major bomb damage (my mum’s school was also bombed … but on a Saturday), compulsorily purchased by the local government, to knock down and build a vital road. A townhouse, he made it a home for the the seven in the family and rented out the top floor. (My granddad was also the youngest of seventeen.)

My granddad smelt a rat. No road would be built, he protested. They were given what equates to £40,000 in current day money (a few thousand back in the 1970s), and today the townhouse – still there, of course – is part of a newly gentrified Peckham, and split into three flats, worth a combined £1m.

What little money my grandparents had left was used up on nursing homes in the final horrible years of their lives, after suffering a combined leg break, hip dislocation and leg amputation (due to gangrene from not getting any physio after a stroke) whilst already in overcrowded and understaffed hospitals.

(My other grandparents only ever rented, on a railway estate, and died when I was young, so there’s no generational wealth; so much for privilege, etc.)

I’d also known from childhood that my mum also died, before I was born; as such, I’m lucky to be here. Again, only in 2021 did I find out the actual details.

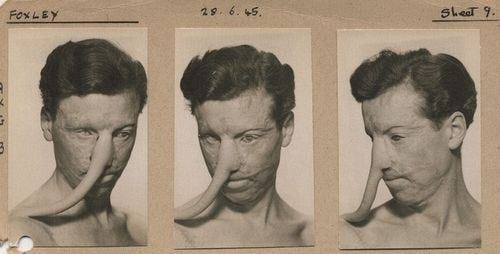

The other major coincidence is that, back in 2004, I had started researching the work of Sir Archibald McIndoe, and his work at East Grinstead in the early 1940s, where, as the country’s preeminent plastic surgeon, the New Zealander developed various incredible techniques to rebuild the faces of burned and broken pilots.

I planned to use it in a novel I ended up abandoning, but reworked part of it for London Skies.

(Brief relevant excerpt below, before article continues.)

1941

Countless blurs of war: memories merged, condensed, concertinaed. Time distorted in both directions in reminiscence, with mere moments living long in the mind and entire weeks lost to the spark of synapses, as if the wiring to a vacuum-tube computation machine frayed and severed, all inputs lost.

In hindsight, East Grinstead, for Charlotte, seeped into an indistinct cloud of several visits, in the half-year between Viktor’s transfer from Brighton and his eventual summer discharge. Icy lawns soon gave way to spring’s banks of daffodils, which themselves wilted in the shade of the budding blooms of buttercups and primrose and bluebells, as summer silently snuck in.

In his midst –– surrounded by the wonders of nature –– were many of the worst burns cases in the country, with airmen at various stages of reconfiguration and restoration and rehabilitation, via pioneering plastic surgery. Like the daffodils, some would quickly die, to be replaced by a more hopeful patient in the assigned plot; a bed, too, in which to flourish or wither.

Charlotte thought she had seen the worst the war could do, but the sights at East Grinstead haunted in a new way. These were patients who, in truth, should not have been alive; a slightly Frankensteinian air of life sparked into deceased flesh, as rapid advances in medicine restored the hitherto too-far-gone.

Men, cursed with crooked smiles and rubbery yellow faces, beset by the droop and list of savage palsies; eyebrows singed away, scabrous scalps where hair had once grown. Men, without eyelids, gazes permanently set to the widest-eyed stare, that left them appearing constantly alarmed, even when smiling. Men, noses as long and pointed as the dishonest Pinocchio, but made of flesh, not wood. Men –– burnt and blistered, patched and plastered –– with the probosces of Bornean monkeys, fat and thick and surreal beneath their eyes. And strangest of all, men, with the trunks of elephants, hanging from the centre of their warped faces, with the tips –– the spouts –– sewn tight to their forearms.

Cheating Death

I hadn’t known that, during the 1966 World Cup – the final of which my dad attended at Wembley (I still have his batch of tickets for all the games, found in his possessions when he died in 2011) – my mum was in traction at East Grinstead, after a near fatal car crash.

As with her sister’s death, it wasn’t something that got spoken about a lot.

She and my dad were no longer together at that point, and she was on a first date with another man (weirdly, an air steward). He impatiently and recklessly overtook some slow traffic in Croydon and went straight into an oncoming car.

(Another coincidence: Croydon was where I eventually studied at the art college, and lived for three years in the early ‘90s, again without knowing my mum’s crash was there. I would have driven through the same junction countless times with no idea.)

My mum wasn’t wearing a seatbelt, but had one arm crooked behind the seat. Knocked unconscious, she suffered a broken cheekbone, nose, jaw, arm and two broken bones in her back, amongst other injuries, and required several operations and skin grafts. She spent six weeks in East Grinstead, her faced clamped up like the character in the novel I was writing.

With her sister having died wearing her jacket a decade earlier, she felt, even as an atheist, that she was being punished for something.

As with her sister, the man driving walked away from the crash, and my grandparents, having lost their eldest daughter, were put through the stress and strain of worrying that they might lose their second-eldest.

Upon waking in their presence, my mum couldn’t stop apologising to them.

The air steward brought my mum some flowers (the de facto gift, clearly, for someone you nearly just killed), but thankfully she never saw him again.

My dad also sent flowers, given that the two had dated in the past, and they eventually got back together, without which you’d be reading something else right now.

The compensation from the crash meant that, a couple of years later, she and my dad could marry and buy a house, right next to the rough estate, instead of in the rough estate, possibly only renting.

I don’t know if generational trauma is passed down in any genetic way, but my dad’s dad spent three years in the Somme in WWI, and returned a shell of a man, before my dad came along a decade later. My maternal grandparents and my mum had the trauma of the death of the eldest daughter, and my mum had the near-fatal car crash.

During her pregnancy with me, my mum couldn’t eat much at all (bar wheaty cereal), and I was born with asthma, eczema, various allergies, and an immune system that probably contributed to my 30 years of chronic illness.

(It used to be a given that the greatest privilege you could have is your health; it’s priceless.)

My mum was ‘lucky’, in a roundabout way. My aunt, less so.

And so I click ‘save’ on this article, and it stores neatly and reliably on my computer hard drive.

Thank you, Mr Tootill, Sir.

London Skies

“A Remarkable literary novel.

A gorgeously written, evocative saga that beautifully explores the enduring impact of fate and coincidence on our lives.

... An utterly compelling literary tale that lingers long after the final page is turned.”

The Prairies Book Review

“An admirably ambitious … and beautifully told story of intersecting lives and histories. Poetic and beautiful prose. The connections across space and time are what really spark and make the novel fly.”

Kirkus Reviews